Crisis Centers and Mental Health: What’s the Plan? : What are we counting?

Idaho has many problems in our mental health system. I have always argued that access to community behavioral health care would save money from prison budgets. There was a good study in 2008 that made some clear recommendations. Starting Crisis Centers* was not one of them.

Governor Otter proposed funding for three Community Crisis Centers in 2014 and I only supported one in the JFAC motion. I sure heard from his representatives that three was what we needed, but they couldn’t answer my questions, so I stuck to my guns, and here’s why. I was hesitant to jump all in for two reasons. First, I suspected if there was a substantial contract there might be a bid from an outside contractor to do the services. I felt strongly that local people should be managing this problem; that’s what’s been shown to work elsewhere. We are trying to address a community need, so why shouldn’t the community have the responsibility? Second, no one could tell me how we would know if this project was working. There were no clear metrics involved in the proposal. What would we be measuring?

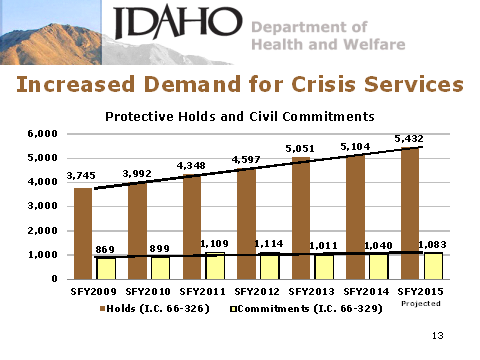

At the committee presentations to support this plan we were frequently shown this graph:

There was no doubt that requests for mental holds was climbing, but the actual commitments were not. This was interpreted at the time to reflect that mentally ill folks in communities were presenting in crisis and we had no good options short of commitment; makes some sense. So would that be the metric we would use to see if this program was working? The first crisis center was sited in Idaho Falls and has been working now for almost three years. But the number of requests for mental holds in Bonneville County (Idaho Falls) last year actually increased even with a Crisis Center. So if that’s the metric, we aren’t spending wisely.

Other states have tried crisis centers and there is some evidence they can save inpatient costs. But when the Crisis Centers were proposed we saw clearly that the number of actual commitments (not requests) had gone up only marginally. So we probably wouldn’t see a real change in that number if they were working.

A further point used to support the Crisis Centers was that many folks with mental illness or substance abuse problems were being incarcerated or jailed. No real numbers were available on jail populations, but we do know that about a third of the prison population is treated for mental illness. It makes good sense that mental health care should be available in the community and if it were adequate and appropriate, we may see less incarceration and folks in jail. Governor Otter sees this now and will ask the taxpayers of Idaho to make a small investment, but only for the recently released from prison. In medicine we call this “secondary prevention”, like treating a guy’s high cholesterol after his heart attack. I believe this is a wise investment. We can count the offenders that are released and return, so we’ll know the value of this effort. Too bad the legislature couldn’t have considered Medicaid eligibility for this population four years ago. I also believe there is a role for crisis centers. But if the evaluation, the data is not clear, how will we know our effectiveness?

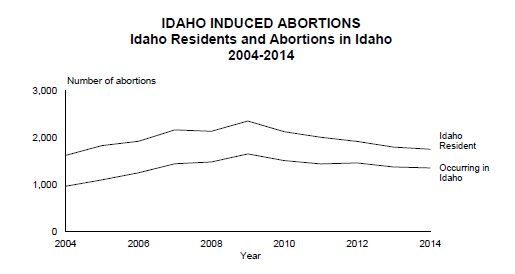

We do measure some things in Idaho carefully. Statute passed in 1977 requires all abortions in Idaho or in surrounding states for Idaho citizens be carefully counted. Consider this graph:

I don’t know if the act of measuring has directly had an effect to reduce abortions, since this actually reflects the national trend. But without the accurate metric, how would we know? Of course, there are those that think this number should be zero. But that’s not management, that’s prohibition. It’s been tried.

In his State of the State speech Governor Otter said voters spoke loud and clear in the last election that they want “government that works”. So let’s do that in mental health services in Idaho. Why shouldn’t the state money going to a regional Crisis Center go along with a requirement that data be collected to reflect the impact of the investment? Each region could tailor their data to their perceived problem; jailed mental patients, inadequate community services, delayed hospitalizations, etc. This would mirror the block grant process the state is begging Medicaid to become. Idaho could lead, instead of kicking the can down the road.

If we are serious about “government that works” we need to be measuring our effort. If it’s important, count it. Otherwise, it’s just throwing money at a problem.

*A Crisis Center is defined in Idaho Statute. They are facilities where a person in crisis may stay for less than one day and receive “evaluation, stabilization and referral”. The statute also requires communities to provide data on the cost effectiveness of the programs. The statute further requires communities to provide support funding “as they are able”. I am unaware of any such reporting or funding to this date.