Our legislative leadership will sometimes schedule events to educate us or augment our skills as legislators. This last session we started with a half day mandatory meeting on civility. I guess they thought we needed the help. Early in the meeting a leader had asked us to consider the concept of integrity. How would we define it? I listened but did not speak. My story would have taken more than a few words.

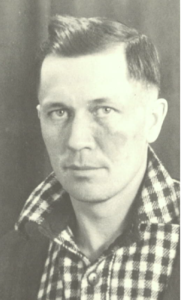

In my thirteenth summer, between eight grade and freshman year at high school I was sent up to Idaho to work with my grandfather.

I’m sure this was my father’s idea and he got begrudging agreement from mom. Dad could see I needed something more than sitting around a Southern California town as my adolescence blossomed. I thought I might spend the weeks on the remote retirement ranch but Henry and Helena had agreed to be range riders for Helena’s cousin on the Cuddy Mountain range. They were familiar with this ground, having the Forest Service range permit before, and when the younger cowboy backed out at the last minute, Henry agreed to push cows over the mountain in his 68th year. And I was along for the ride.

They got me a good cow pony, Ginger, and I was on her every day. From the first time Henry saw me horseback he instructed, “Sit up straight, goddamit, yore gonna lame yore horse.”

I straightened my back and later asked what my posture had to do with a horses hoofs. “It’s all tied together dammit.” He’d smile. “She’s as reliant on you as you are on her. You sit crooked or slumped like a wet noodle, she’s not gonna walk right. She’ll go lame. Hell, I seen it.” He didn’t mind my honest question. I worked on my saddle posture.

We were up on Cuddy Mountain for three weeks moving cows from one side of the high mountain range to another. On our second to last day up there Henry called me out from the line shack. I did the dishes each morning in the wash basin on the wood stove and Helena dried while Henry saddled the horses.

“Dan, get out here!”

Helena said, “Uh oh.”

I came out with a dish rag. He was mad.

“Now I’ve tole you and I’ve tole you about sitting up straight. Look it what you done here.” He pointed to a small lump on my mare’s back. “Feel it.” I could feel it was swollen. “That’s what I been telling you. If you’d sit up straight this wouldn’t a happened.”

I blinked back tears of shame and said I’d do better. We left camp with the sun in the eastern trees, a warm day, me sitting straight but holding back. As we headed off to some grassy meadow where I knew not, Henry dropped back from Helena and came up beside me.

“When I saddled your mare this morning after I yelled at you I saw where the skirt on your saddle had been folded over yesterday when I saddled her. So that lump was my fault, not yours.” I looked over to his shadowed face under the stained felt hat. He grinned at me, the Bull Durham cigarette in the corner of his mouth. “You still need to sit up straight.” I nodded.

I’ll never forget my grandfather’s integrity. He had no need to set the record straight, owning his own mistake, to tell his teenage grandson the truth. But he did. And I’m better for it.

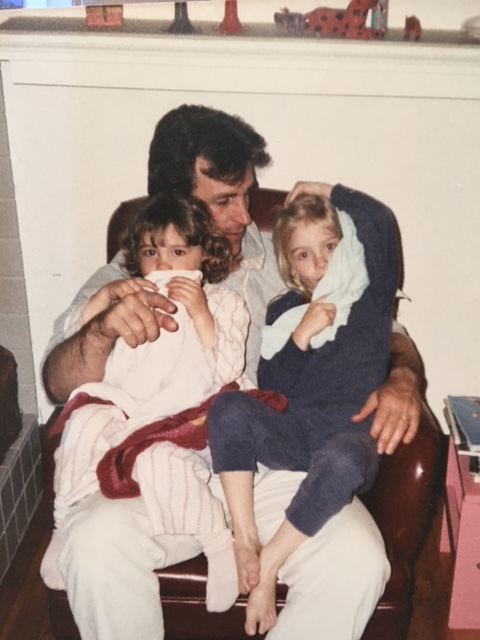

That fall, my father brought me in to the kitchen after a Friday freshman football game; I thought it was to be the usual rehash of what I could have done better, for Dad put great stock in my athletic future. But he told me that Henry had died on Thursday. He’d had a stroke on Wednesday and they took him to town but he died there in Council the next day. Dad said he waited until after the game to tell me so I could stay focused. I wished I would have known sooner.

We pass on so many things to those we love, to those we touch, ones we see every day. But the lessons we learn stay after. As I head into this advanced age I cherish the examples of wisdom and strength, and indeed the weaknesses and judgement of my fathers before. May I be so able.