Maybe you’ve heard the statistic quoted that Idaho is last (or near) among states in doctors per capita. If medicine was a simple business that ratio might mean the dearth of physicians would ensure doctors in Idaho are among the best paid, supply and demand being what it is. But in fact, Idaho doctor salaries are about average to below average. Medicine may be a business but the economics are complicated.

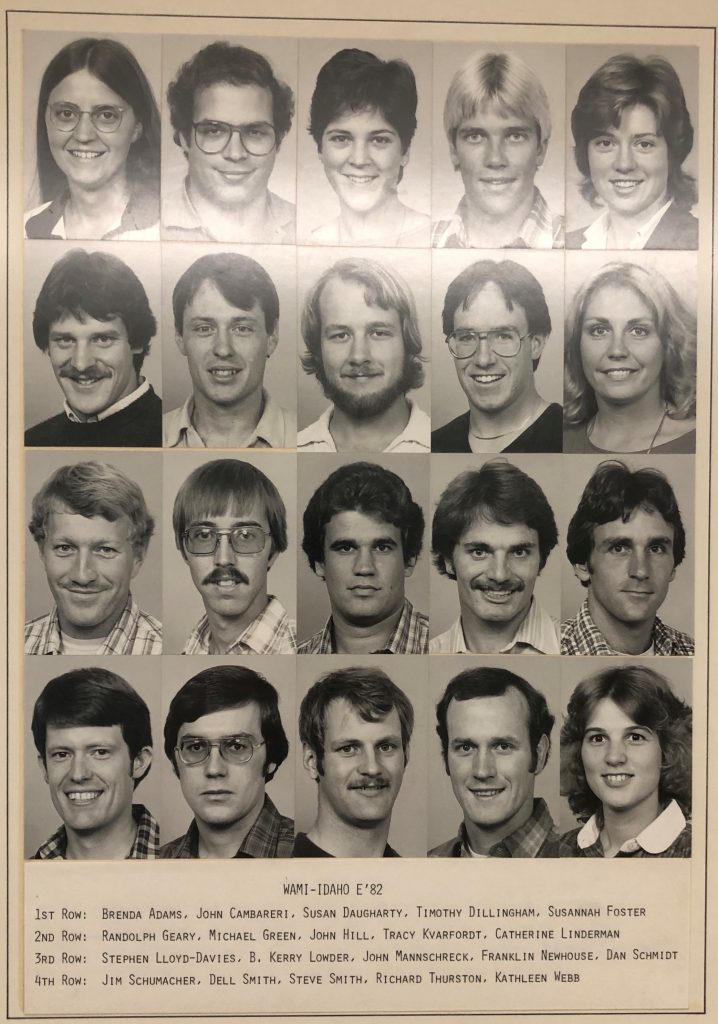

Former Governor Otter’s commitment to boosting medical education in Idaho was supported in the legislature when I was there. In that tenure, the Idaho WWAMI program grew from 20 seats to 40. WWAMI is a medical education consortium of 5 states: Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana and IDAHO. Those 40 seats are reserved for Idaho resident applicants. Idaho students now spend their first year and a half of the four years of medical school in Idaho. Many are based in small towns and rural communities, learning from the local physicians and patients about managing disease and chronic illness.

Medical training takes many steps. After receiving a bachelor’s degree (usually a four-year process) the next step is four years of Medical School. Then there is the residency step that takes 3-10 years, depending on the specialty one chooses. After residency docs go hang a shingle and see what they will be paid. Most doctors in Idaho make over $150K, so it’s not a shabby income. But many could do better elsewhere; market forces are real.

But for most doctors it’s not just the money that motivates. Most want to serve; their patients, serve their communities, serve their profession, serve their families. Unfortunately, many doctors put their service in that order. Families can suffer. If you are a small community in need of a doctor, think about what you can do to make a family thrive in your community. Could the schools be better? Do you have a good library? Do you have opportunities for a spouse, a family to thrive? Doctors will like such opportunities; so should you.

But getting a doctor is just part of the process. Keeping one and keeping them good is another. The Idaho WWAMI program is not just about running students through the four years, they are also committed to supporting doctors in small communities stay strong, stay informed, practicing good medicine.

Two of the toughest fields of practice for rural family physicians is behavioral health (the new term for psychiatric-emotional-personality-addiction problems) and chronic pain. The explosion Idaho and our nation have seen in overdose deaths from narcotics is just one indicator. Docs haven’t been doing the best managing pain. And most psychiatric care in Idaho is provided by primary care providers; we are last in the country for psychiatrists and behavioral health specialists. WWAMI saw this need and responded.

Two years ago, WWAMI set up the ECHO program. Providers (physicians and nurse practitioners, physician assistants, social workers or counselors) participate remotely in an interactive online session to discuss the difficult problems they face. The sessions focus on how to prescribe narcotics appropriately and managing behavioral health. Such support will go a long way to keeping providers at the top of their game in this rural and frontier state.

We hear about the cost of care, Medicaid and Medicare, who pays and who doesn’t. There is no doubt that the medical industrial complex has a strong presence in “the swamp” as our president refers to the business-political morass. And I’m sure there’s plenty of ideas about how to get out of this mud hole. Payment affects behavior; sometimes. But we, in our communities can make health care about being healthy. I would hope our dear state of Idaho has such a vision.